10 May 2021

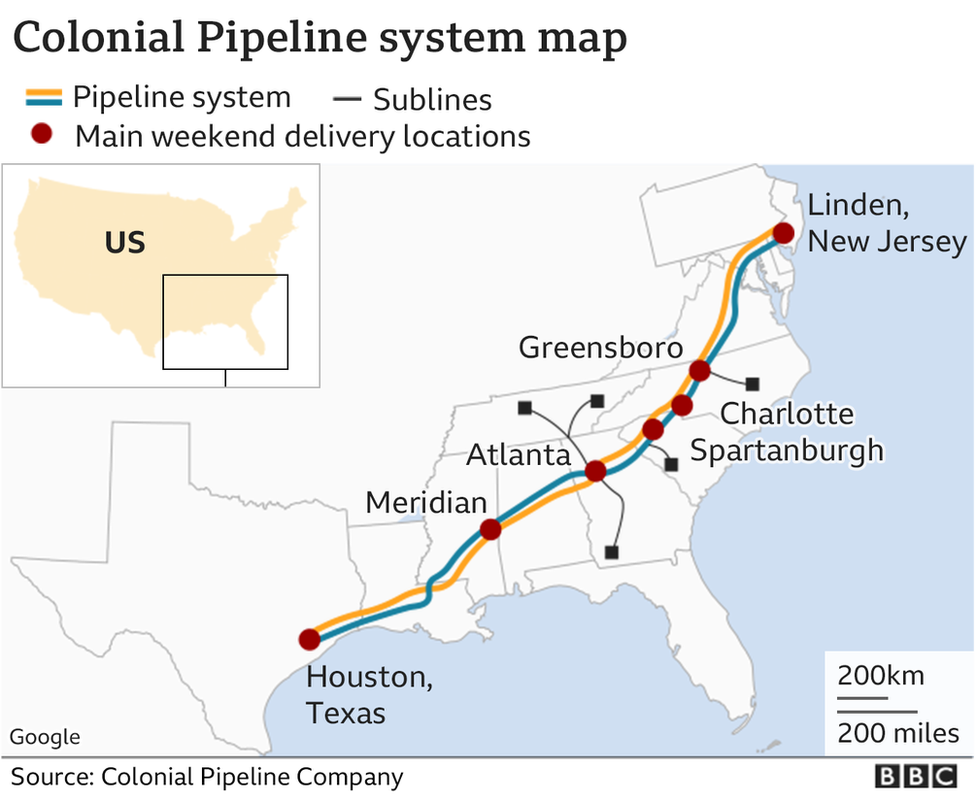

Investigators at the largest fuel pipeline in the US are working to recover from a devastating cyber-attack that cut the flow of oil.

The hack on Colonial Pipeline is being seen as one of the most significant attacks on critical national infrastructure in history.

The pipeline transports nearly half of the east coast’s fuel supplies and prices at pumps are expected to rise if the outage is long lasting.

How can a pipeline be hacked?

For many people, the image of the oil industry is one of pipes, pumps and greasy black liquid.

In truth, the type of modern operation Colonial Pipeline runs is extremely digital.

Pressure sensors, thermostats, valves and pumps are used to monitor and control the flow of diesel, petrol and jet fuel across hundreds of miles of piping.

Colonial even has a high-tech “smart pig” (pipeline inspection gauge) robot that scurries through its pipes checking for anomalies.

Image source, Colonial Pipeline

Image source, Colonial PipelineAll this operational technology is connected to a central system.

And as cyber-experts such as Jon Niccolls, from CheckPoint, explain, where there is connectivity, there is risk of cyber-attack:

“All the devices used to run a modern pipeline are controlled by computers, rather than being controlled physically by people,” he says.

“If they are connected to an organisation’s internal network and it gets hit with a cyber-attack, then the pipeline itself is vulnerable to malicious attacks.”

How did the hackers break in?

Direct attacks on operational technology are rare because these systems are usually better protected, experts say.

So it’s more likely the hackers gained access to Colonial’s computer system through the administrative side of the business.

“Some of the biggest attacks we’ve seen all started with an email,” Mr Niccolls says.

“An employee may have been tricked into downloading some malware, for example.

“We’ve also seen recent examples of hackers getting in using weaknesses or compromise of a third-party software.

“Hackers will use any chance they get to gain a foothold in a network.”

Hackers could potentially have been inside Colonial’s IT network for weeks or even months before launching their ransomware attack.

In the past, criminals have cause mayhem after finding their way into the software programs responsible for operational technology.

In February, a hacker gained access to the water system of Florida city and tried to pump in a “dangerous” amount of a chemical.

A worker saw it happening on his screen and stopped the attack in its tracks.

Similarly, in winter 2015-16, hackers were able to flick digital switches in Ukrainian power substations, causing cuts affecting hundreds of thousands of people.

How can this be stopped?

The simplest way to protect operational technology is to keep it offline, with no link to the internet at all.

But this is becoming harder for businesses, as they increasingly rely on connected devices to improve efficiency.

“Traditionally, organisations did something known as ‘air gapping’,” cyber-security expert Kevin Beaumont says.

Image source, Colonial Pipeline Company

Image source, Colonial Pipeline Company“They would make sure that critical systems were run on separate networks not linked to outward facing IT.

“However, the nature of the changing world now means more things are reliant on connectivity.”

Originally Found On BBC And Submitted Anonymously Over Email